The Story Of How One Man’s Life Was Reinvented To Create A Mythical Late 20th Century Musical Genre

To many British readers, this review is going to be controversial for which I make no apology. However, I must stress that despite how uncomfortable this might be for some, I am only ‘the messenger’ for a story that has surprised me, as much as it may shock and offended others.

To many British readers, this review is going to be controversial for which I make no apology. However, I must stress that despite how uncomfortable this might be for some, I am only ‘the messenger’ for a story that has surprised me, as much as it may shock and offended others.

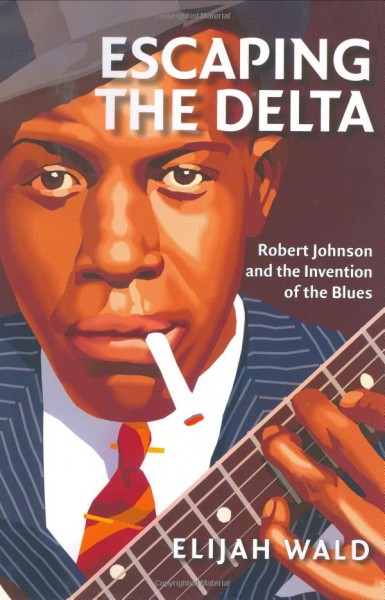

Within the pages of this book first published in 2004, Elijah Wald candidly lifts the lid on a musical movement spawned under the illusion of folklore and myth promoted by a later 20th century generation of White Europeans. From a personal perspective as a musician who has played in a band suffering the puzzling indifferences of the British ‘Blues’ scene for some years, I will declare that I do have a justifiably and indisputable axe to grind. None the less, this book has provided answers to my bewildered train of thought, finally giving me the closure and clarity to move on as a musician and listener.

Like most White folks living in England, I was under the impression that ‘Blues’ music was all about Black folks living under hardship, slavery, misery and knowing only their African musical roots. They would gather and listen to mysterious Blues men, hollering out songs of destitution, having fallen on hard times under the influence of liquor and selling their souls to the Devil at some desolate crossroads in the deepest, darkest area of the Mississippi Delta. These Blues men would be dressed in ragged clothes, bare foot, sitting on the porch of some scruffy shack house, playing a battered under-strung guitar, sliding the strings with a broken neck from the top of a whisky bottle, whilst a group of equally impoverished Black peasant workers sat listening intently, feeling their spirits elevate to a joyous state as the Blues shouter shared his stories of woe and misfortune.

If that paints a picture you would like to associate with ‘Blues’ then be prepared for a cold, harsh wake-up call. Elijah Wald pulls no punches as he dispels the myth of a genre that never really existed as a post 1960s Europe reinvented it. He also makes no apologies for drawing on factual information already written elsewhere – but this is absolutely necessary to piece together his case with documented references to real events.

Not an easy read, even for music aficionados; Wald covers a lot of ground with all the necessary details making it more of a dissertation than something you may want to put on your Kindle on a foreign beach vacation. However, if like me you have an intense urge for answers driven by years of frustration from trying but not understanding the British music consumer psyche, then the rewards from persevering through the chapters of this book are pure redemption.

Revelation #1 – There Is No Such Thing As ‘The Blues’

Well, there is – and there isn’t; it depends how you want to see it. Pre Chess Records, the music made by Black American musicians was deemed as ‘Race’ music. Wald’s research covers all the early incarnations of what we deem today as ‘The Blues’ – WC Handy, Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey et al (it’s pointless going through the full list, read the book!) He uncovers an entertainment circuit in the Deep South – further afield – where there was a high concentration of Black working people who like White working people, sought entertainment. This circuit consisted of the many ‘legendary’ Juke Joints and more surprisingly, theatres, worked by Black entertainers from the early years of the 20th century up to the 1940s. Like today, working people at the end of their week simply wanted to dance, drink, have fun -maybe get laid – and musical entertainment provided a background to do this to. Theatre shows were pretty much Vaudeville concerns with big bands fronted by equally large, brassy, sassy female singers. These ladies were big on voice and big on stage presence, singing whatever songs were popular of the day and in the regional Black entertainment world, they were considered as much ‘stars’ as we regard the ‘celebrity’ entertainers of today.

It is surprising to learn that there were no male singing ‘stars’ until a bit later on and the ones who did emerge all had to try and imitate the style of Ma Rainey and her like! There was no particular ‘genre’ that these singers worked under; they were simply, entertainers. Shows would feature any number of different styles – they might sing ‘a spiritual’, they might sing ‘a blues’, they might sing Bluegrass folk, they might sing Ragtime and they might even sing a Hillbilly Hoedown tune accompanied by Black musicians playing Fiddles! That was a huge revelation for me, as somebody who always (mistakenly) believed that Black people only ever played music that solely had its roots in African tribal song and rhythm! This I now realise, was a myth perpetuated (in the best intentions) by the White Black music folklorists of the 1940s, in their attempts to bring ‘Race’ music into the consciousness of the White Americans who were already showing a closeted interest in the songs made popular by their fellow countrymen forced to live as second class citizens. These folklorists and archivists for whatever reasons, focused their research to a very limited spectrum of musical styles sung by Black entertainers, in particular, the rural songs sung in ‘a blues’ style recorded in the early 1930s. The researchers seem to have been fixed on recording every field worker slave-song rather than what was being played in the Juke Joints of the time. Hence, we are left with the most documented style of song associated with early Black singers being the ones sung in ‘a blues’ style, which is just the tip of a bigger iceberg of musical styles.

It’s Not About Poverty, It’s About The Money!

The theatre entertainers Wald talks about were all professional, well paid artists at the top of their game. If you weren’t entertaining in theatres, you were working the Juke Joints, aiming for the big time, hoping for your big break from a visiting talent scout who may just be in the audience. The 1930s Juke Joints seemed to be a lucrative earning ground for the rural style ‘Blues’ entertainers like Leroy Carr, Son House, Kokomo Arnold etc, etc; and of course, Robert Johnson who was greatly influenced by these people. However, like the theatre entertainers, these Juke Joint stars were also highly professional, skilled performers, well paid for their work and perhaps most importantly, singers of every genre and style of song that was popular of the day – not just ‘Blues’ styles.

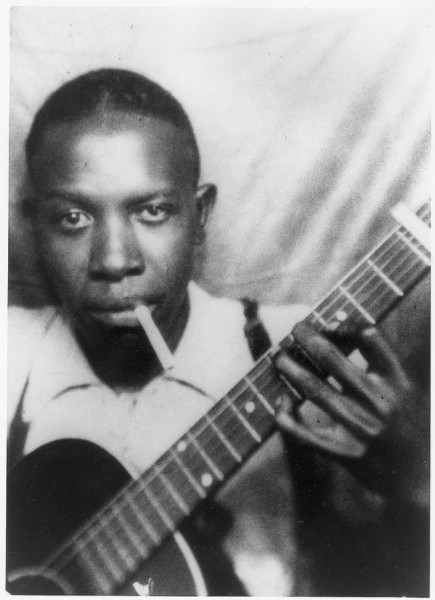

The remarkable thing (again overlooked by folklorists) about Robert Johnson, was his incredible ability to imitate different styles to please any audience, a requirement of any Juke Joint entertainer whose job depended on keeping people dancing. Even if you limit a comparison between the different blues styles of say Son House and Leroy Carr – both artists Johnson could skilfully imitate in performance – it is insulting and wholly inaccurate to limit Johnson’s talent just to one genre. Although ARC records chose to record Johnson singing the rural ‘Blues’ style at a time when that style was waning in popularity, Johnson was certainly singing a much wider range of styles in his ‘day job’ than captured on his recording sessions. Wald’s documented research irrefutably supports this, highlighting the modern misconceptions grown around Johnson and the so called ‘birth of the Blues’.

Wald testifies that rather than the poor, mysterious Bluesman we are led to believe Johnson to be, he was in reality, an extremely skilful, ambitious artist, wanting top dollar for his work, desiring the finery and riches obtainable through mass popularity and eager for his big break into the theatre circuit. Ironically, this may have happened had he lived to play John Hammond’s New York ‘From Spirituals To Swing’ concert in 1938.

This particular coverage about Johnson’s life in the book left me questioning whether had he lived and achieved the same level of success as say, Louis Jordan, would he have been singled out as the main artist responsible for turning a 1960s European youth movement onto forgotten Black American rural music?

Modern Day Fall-Out

Chapter 14, the final one in the book, is undoubtedly the ‘killer’ chapter. Within these pages, Wald delivers everything that is wrong and bad about the modern, worldwide ‘Blues’ scene, a result of inventing a movement on the back of one particular style of song that wasn’t even over-dominant in the lives of the people who are credited with inventing it. Instead, Wald offers an alternative and sobering viewpoint, explaining how 1960’s Europeans took almost forgotten Black American artists who were still working as entertainers – not playing too many of the songs they played in the 1930s –importing them to Europe and asking them to resurrect the styles found on two Robert Johnson albums that Eric Clapton happened to consider the most important recordings ever made. Wald’s research uncovers these artists questioning why anybody would want to hear that old forgotten stuff again when Black music had vastly moved on with the Civil Rights movement, but seeing a pay cheque and a trip to Europe, they delivered the goods. Well, they delivered a bit more than what the young White hipsters bargained for, in particular, T-Bone Walker’s appearance in Germany in 1962 offers a humorous account of how he was asked to tone down his stage show and lose the stage antics because the audience had come to sit at the artists feet and witness a ‘serious’ performance! That one story alone is enough to reveal how Europeans got the whole history of Black American music so, so wrong, completely disregarding the fact that these people were primarily, entertainers booked in their homeland to give a proper vaudevillian show for their money! Look at the footage of Muddy Waters at the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival; what to you see? Do you see a scruffy hobo singing dolefully about getting his ‘mojo’ working, or do you see a sharp suited, professional, business-like entertainer delivering a well-rehearsed on-the-money show? That footage has more in common with Louis Jordan or James Brown than a rural, bare-footed southern peasant.

And this is where it all goes horribly wrong, in musical evolutionary terms at least…

With all the possible styles of music that Robert Johnson, his predecessors and musical ancestors chose to perform to entertain (remember that word folks, lest you forget), why, oh why, have we been left to boil out the bones of just one of those particular styles and moniker it with a modern musical genre of its own? Yes, we still have big names from the post 1940s Chicago Blues world to fall back on – the Kings, Waters, Diddley and such – but their collective styles have little to do with a modern world, intent on ego-centric guitar-slinging to fill time, in comparison to Robert Johnson who would repeat verses or make them up on-the-fly, just to keep an audience dancing.

Wald hits on a superb observation about the dilution of the modern post-60s Blues revivalist genre, what it’s become and who it preaches to or more pertinently, the size and type of audience it seeks to serve. He makes a case for the modern Blues audience now having shifted from Black to White with limited numbers. As a musician himself, he will have seen this first hand in America, as I have in England – though in a much smaller capacity. He suggests that smaller audience sizes can only feed off and support a small talent pool. The smaller the talent pool, the fewer demands the equally small audience will make, giving rise to mediocrity becoming the norm within the genre – even when the musicians are capable of doing better. If the audience aren’t there to demand it in high numbers, then the envelope will never be pushed. He paints a landscape where we are left with post Stevie Ray-Vaughan guitar-slingers substituting guitar histrionics to the detriment of developing new vocal styles and song, with only a handful of artists keeping the latter skills at the forefront of their craft.

As somebody who has been trying to naively plough through the UK Blues scene for over 7 years with my own band playing our diverse range of Black American musical styles, Wald’s observations were a huge personal epiphany, providing an answer for my own disillusionment with an extremely myopic musical clique. Finally, I could now understand why I didn’t fit into the last remaining outpost of the post 1960s British ‘Blues’ revivalist scene, or why my teenage children would never consider buying tickets for a ‘Blues’ festival, let alone downloading any material by the handful of teenage guitar-guns who have been passed the mantle of ‘keeping the Blues alive’ by a sexagenarian fan-base.

On the other hand, consider this. Taking Wald’s research as a guide, what if Robert Johnson’s body had been cryogenically stored and resurrected in 2014 to carry on where he left off? Do you think he would jump back into a declining audience base on the modern post-1960s ‘Blues’ revivalist circuit to enjoy critical acclaim and its extrinsic rewards; or do you think he’d go back to doing what he did when he was alive, entertaining his own demographic, putting feet on dance floors and chasing the money? I would suggest the latter, with a 21st century Johnson more likely to be seen belting out the latest Pharrel Williams or Bruno Mars hit over a minority appreciation of ‘Dust My Broom’.

And What About The Devil?

Yes; that folkloric tale about a Johnson who sold his soul to The Devil at some crossroads…well, in true Wald myth-busting style, it is revealed that there was a Johnson who supposedly sold his soul to the Devil – but his first name wasn’t Robert. I won’t reveal who is named because if you’re still reading this and want to know, you really need to read the book. Besides which, the ‘selling of one’s soul’ to gain greater powers over a particular skill was a widespread hokum anecdote told about any performing artist who excelled at their craft in the Deep South of early 20th century America. Just add Robert Johnson to a cast of many, it wasn’t a unique accolade amongst his peers.

Let The Juke Boxes Tell The Truth

Perhaps the most simplest and revealing part of the whole book is the appendix section, itemising the song lists of Juke boxes for five African-American bars in Clarksdale Mississippi, documented in 1941 by the Fisk University Library of Congress team. If these are anything to go by, the quantity of Black rural style ‘Blues’ is absolutely miniscule in comparison to the popular dancing songs of the day. These Juke boxes do not reflect a local population sitting around sedately, milling over their hard day’s work, crying into their liquor, listening to songs about when they’ll be one day set free. No, this is a collection of songs for jumping, jiving and feeling as good as it gets at the weekend. If you want a modern day comparison, then think ‘Happy’ by Pharrell Williams as your starting block and go from there.

So Where Did We Get It So Wrong?

It’s just a pity that the European rural folk revivalists chose such a restrictive view of pre-war African-American music to import into the psyche of White music listeners in the early 60s. Had they been able to travel to America and perform their own research, a whole spectrum of musical styles would have been presented to them as a representation of early African-American culture, rather than just a one-trick pony style. Hence, thanks to this narrow cultural vision, we have been left with a recently created musical genre, based on one style of song structure amongst a gamut of others that has long peaked in popularity, to be rehashed into an extremely limited format and consumed by an equally limited music buying demographic.

My review of Elijah Wald’s comprehensively researched work is not intended to denigrate the artists of the early 20th century who have left us with a rich legacy of recordings of just some of the styles of songs they performed throughout their careers – far from it. As an educational book covering the effect a small element of African-American musical history had on post-war Europe, it answers many questions one might begin to ask when trying ascertain why the British ‘Blues’ scene of the 21st century fails to deliver in a diversity of styles and equally fails to capture the imagination and interest of the mainstream music consumer.

As a musician who has struggled to understand the indifference shown by the UK Blues market towards the diverse range of historical African-American music styles, Elijah Wald has finally unravelled a mystery that has been obfuscating my search for the truth behind the musical genre known as, ‘Blues’. On the other hand, perhaps I have misinterpreted my own experiences? Maybe British audiences really do enjoy sitting and listening to White musicians with guitars and harmonicas, reinventing a singular theme? Whatever ‘the truth’, I’d rather be on my feet to Louis Jordan with the African-Americans of 1941 Clarksdale.

It is certain that not every reader of Wald’s book will draw the same conclusions, no doubt continuing to enjoy the 21st century ‘Blues’ scene for what it is and for how ever long it lasts. But, for me, it has provided the final testimony needed to escape from what has become an uncomfortable coffin and to move on with my journey to discover the rich assortment of musical styles that make up African-American music history.

(This article was originally published on the Blues In The Northwest Website.)

Elijah Wald and I are having a conversation about his Robert Johnson book and his claims in it about where blues music originated (he used _… And The Invention Of The Blues_ in his title, but doesn’t understand who invented blues music) on amazon right now. Here is the conversation so far:

Scott:

The great majority of this book deserves five stars, and one of the main points it makes deserves one star. Wald is interested in Robert Johnson in his ’30s context and does a terrific job of describing that context. Wald seems to have far less knowledge of blues music before 1920, and his suggestion that blues music did not arise as folk music goes against a mountain of evidence that it did, including from people who were old enough to observe it doing so such as W.C. Handy. (Of course that idea sounds interesting to any reader who is excited about blues music being demythologized. But it isn’t true. Folklorists Howard Odum and E.C. Perrow independently collected black folk songs with the word “blues” in them _years_ before Handy’s “Memphis Blues” was published. If song publications anywhere in the South or North and a consensus among Handy’s peers don’t satisfy you, read e.g. Abbott and Seroff’s books and Henry Sampson’s comparable book and notice when minor stage performers began taking up “Blues” at all. Peter Muir’s book is important for context too.) When I corresponded with Wald about this, he forthrightly admitted that he couldn’t defend that idea well. I hope it will be omitted from any future editions of the book.

Wald:

I would only note that Lynn Abbott (of Abbott and Seroff) read the chapters on pre-blues, contributed to them, and does not share Joseph Scott’s opinion of them–which is not to say he agrees with every word, but he does not think there are substantial errors of fact. Whether blues was a form of folk music is a matter of interpretation, not of fact. My interpretation remains the same as in this book, though I thoroughly agree that other interpretations are possible.

Scott:

Where blues music originated is a factual issue. The New York Times online quotes you as saying in 2004 that “the blues was pop music — it simply wasn’t folk music. It was invented retroactively as black folk music….” That radical statement is simply wrong, and shows ignorance of the research that was done on early blues music during the 90-plus years before it. Howard Odum and E.C. Perrow, working independently of each other, both published black folk songs in the 1910s that were collected before 1910 and were specifically about having the “blues.” This book claims on p. 32 that “[m]ost likely” folk artists did not have any more primacy than pop artists. If that’s so, then according to you, Elijah, what similarly important role did pop artists most likely play before 1910 in the invention of blues music?

Scott:

I’m mystified what it is that Lynn Abbott agrees with Elijah Wald about that is supposedly relevant to the critical element of my review. From Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff’s “‘They Cert’ly Sound Good to Me’: Sheet Music, Southern Vaudeville, And The Commercial Ascendancy Of The Blues,” emphasis added: “Clearly it was at the insistence of the southern vaudeville audiences that the blues, a previously submerged aspect of African American _folk_ culture, ascended the stage…. When southern vaudevillians embraced _folk-blues_ concoctions in their stage repertory, the audience shouted loud in recognition….” “Blues and other timber hewn from rural southern _folk_ culture had served as [black stage entertainers’] battering ram [into larger theaters].” “… John H. Williams specialized in the comic adaptation of the up-to-date Southern _folk_ idioms from which blues was gleaned.” “String Beans, Baby Seals, Johnnie Woods [who is the first person documented singing blues on a stage, in 1910] and Little Henry, Willie and Lulu Too Sweet, Laura Smith — these were some of the first ‘blue diamonds in the rough’ [quoting W.C. Handy, who said blues music originated as folk music] to rise above the anonymous street corners, barrelhouses, juke joints, railroad depots, and one-room country shacks of _folk-blues_ literature. They were the fathers and mothers of the blues on the American stage.” “The implication is that by 1909 the term blues was known to describe a distinct folk-musical genre….” From Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff’s _Ragged But Right: … The Dark Pathway To Blues And Jazz_: “By mid-decade [of the 1910s], blues singing had begun to make a permanent home in tended minstrelsy [by black performers]. W.C. Handy’s early blues publications [which started in 1912]… initiated the trend.” “Prof. John Eason’s Annex Band [a black band]… may have been the first circus band to include a blues song in its repertoire… [in] 1912….” Where is the evidence that pop music was contributing to blues music during the period 1905-1909? Because 1905-1909, that is the period when Antonio Maggio said he heard a black guitarist on a levee perform an “I Got The Blues” that served as the inspiration for the 12-bar strain in his own published “I Got The Blues,” _and_ a black folk song with “blues” in the lyrics was collected that E.C. Perrow reported on in his _Journal Of American Folk-Lore_ article, _and_, independently of Perrow’s work, Howard Odum collected more than one black folk song with “blues” in the lyrics (see his “Folk-Song And Folk-Poetry As Found In The Secular Songs Of The Southern Negroes”: “I got the blues but too damn mean to cry/I got the blues but too damn mean to cry” in “Look’d Down De Road” and “I got de blues an’ can’t be satisfied/Brown-skin woman cause of it all/Lawd, Lawd, Lawd” in “Knife-Song”). When that collection of Odum’s appeared in book form in 1926, the book said, “[These lyrics] are taken from songs collected in Georgia and Mississippi between 1905 and 1908…” and “There is no doubt that the first songs appearing in print under the name of blues were based directly upon actual songs already current among Negroes.”

For me, the original origins of the style were less important to me than its relevance as the ‘sole genre’ it was reinvented as in the latter part of the 20th century. No doubt from what you say, there is unfinished business regarding the absolute origins of the style which I am far too unknowledgeable to participate in!

However, as a white British person born in the 60s, who formed his own distorted view of early African-American involvement in the creation of modern music genres, it was an eye opener. It’s easier to piece together post 1920s music history than what preceded that, but I’d never bothered to, simply relying on the latter European generated folklore covering the origins of Black American music. It was another musician friend I work with from time to time who put me onto this book after informing me that my preconception of Black people only ever playing music exclusive to their culture was wrong. Whatever the problems with the pre-WC Handy period Wald may have overlooked, there appears to be a lot of evidence provided to support the suggested fact that Black American musicians would play every kind of music as professional entertainers, not just one genre as my generation have been led to believe.

I guess my interest isn’t as an early historian, but more from a standpoint of finding out why ‘Blues’ as a standalone genre doesn’t work on a wide commercial basis for a mainstream audience. Thus, Wald’s book certainly helped put a lid on a lot of confusion for me. However, I can see from your conversation on Amazon, the historical debate at the opposite end of the time scale will rage on…

Thank you for the input as well, it will be interesting to see whether Wald does release an errata edition in the future – if people are still buying books!

Hi, the stuff about Robert Johnson in the book is great, which is why I gave the book four stars on amazon, despite this pre-Robert-Johnson (literally!) issue that he dropped the ball on in the book and in promotion of the book and is still dropping the ball on at his website.

My conversation with Elijah in the amazon comments continued. Elijah (who in 2004 said blues music “simply wasn’t folk music”) acknowledged on Dec. 1, 2014, “It is… clearly true that ‘blues originated from old… folk lore songs.'” (The quaintly worded quote is from black pro songwriter Perry Bradford in 1921.) He acknowledged on Dec. 8, 2014, “I think that many of the folk songs [Howard] Odum collected before 1909 are what I now would call blues music….” On repeated requests, he didn’t offer evidence for his notion on his website, “first [blues] was a black pop style…,” because he can’t, because it wasn’t. The first publication of a blues song wasn’t until 1912 (by the black pro songwriters Chris Smith and Tim Brymn, copyrighted in January 1912), at least 3 years after Odum, according to Odum, stopped working on that particular collection of black folk songs. (There was a single “Blues” instrumental published before 1912, by a white guy who later recalled that he’d picked up its basic 12-bar strain and its title from a black guitarist on a levee.) As of now Elijah has not changed that inaccurate claim at the website.