My Close Encounter with Boon Gould – Close but no Cigar

It seems these days, my only inspiration to write is when somebody I admired from afar passes onto the next journey of our energy time-line. On the last day of April 2019, the news was released that Rowland Charles ‘Boon’ Gould, former guitarist of Level 42, older brother to ex-Level 42 drummer Phil Gould, was dead.

Found at his home in Dorset aged only 64, one naturally speculates on the possible cause of death; a sudden demise alone can suggest cardiac arrest, freak accident or the unthinkable, death by one’s own hand. I am reluctant to expand on my suppositions as there is the private grief of the Gould family to consider, but from what has been mentioned in the public domain about Boon’s personality, there is more than a suggestion of personal anxiety affecting a portion of his life.

Sometimes, for those who suffer long-term within an oppressive mindset which cannot be conquered, a drastic exit can seem the only road to a final state of inner peace. On a personal note, one of my childhood friends took his own life a few years ago, much to the shock of those of us who could only ever remember a cool, good looking, happy, ray-of-sunshine-of-a-kid, shining his infectious mischievous streak whilst we explored our 1970s playgrounds.

It’s not my place to speculate about how Boon Gould left us and neither is it any of my business. I can only echo what Mark King wrote on Twitter, “…no more pain…” and hope the Goulds find some comfort in the knowledge that the subject of their loss positively contributed to the soundtrack of many young lives, including mine.

Once Upon a Time in Liverpool…

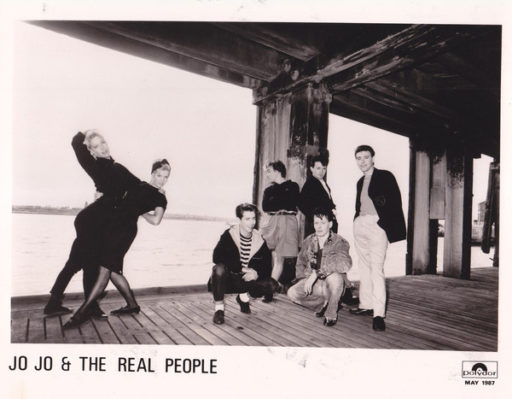

…lived a pair of old school Scallies named Mick and Bob with a keen eye for the Liverpool music scene. The year was 1986 and the British music industry was flowing with cash to invest in new young artists. Mick and Bob ran a music management company and were looking after the business interests of a band called Jo Jo and the Real People.

Between the pair, Mick was the supreme hustler, the cheeky scouser who chased advance money on the telephone to London A&R men who probably felt slightly intimated, but comfortable enough to engage with Mick’s band auctions.

Mick and Bob didn’t aim low and it wasn’t long before they landed both publishing and recording deals for Jo Jo and the Real People, the latter deal with Polydor Records.

Also-Rans on the Coat-Tails

There just so happened to be another band in town, who also fancied a piece of the action Mick and Bob were generating. Unashamedly commercial in sound, seeking fame, fortune and associated vacuous pursuits, I had thrown my self-serving lot in with them as their drummer.

The way I conducted myself in this group looking back on it, was quite toxic, leaving me ashamed to this day of my complicity in two acts of removing band members; but that’s a story for another day.

The band had been foisting themselves on Mick and Bob’s office for months, handing out demos and trying to convince them to do the same for us as they’d done for Jo Jo and the Real People. We were no doubt equally as precocious as we were annoying and eventually they passed us on to one of their associates, who also wanted to get into band management.

Barney (not his real name) was a slightly chubby man of about 30, with balding red hair and a pair of large spectacles, synonymous with the style of the ‘Yuppies’ during the mid 1980s. He exuded enthusiasm for our commercial potential and wanted to start working with us as soon as possible. He also owned an ugly French ‘people carrier’ vehicle, possibly one of the first of its kind from the era.

Barney Goes to London

Some time during early 1987, an opportunity arose for us to attend the launch gig for Jo Jo and the Real People’s début single, a cover of the old Patti Labelle hit, ‘Lady Marmalade’. The story was, Polydor had sunk a fair bit of cash into their new signing and wanted to see what they were getting for their money.

The showcase gig was set to take place at The Limelight club on Shaftesbury Avenue in London, in front of Polydor execs and other luminaries of the music business. Barney asked Mick and Bob if it would be okay for us to come to the gig and mingle backstage afterwards. There was even a rumour that members of fellow Polydor artists Level 42 were going to be there, which raised our excitement levels off the scale. The new Bass player in my band was as much of a Mark King fan as I was of Phil Gould, so we couldn’t wait to see the day when we’d be travelling down to the gig. Preparing to sell his new prodigies to whomever may be present in London, Barney had armed himself with a clutch of our demo tapes, ready to pounce on anyone who might be useful during the after-show.

From a prime position on a balcony, we jealously watched what was a well received gig for Polydor’s potential new cash-cow. Our viewpoint gave me a perfect spot to look on enviously at ex-China Crisis drummer Dave Reilly, in a position I desperately wanted to be in, playing in front of important people from the label my band was signed to. But I took comfort by reminding myself at least I was ‘in the swim’ where the opportunities for my band to network couldn’t get much better.

Backstage Nerves

As soon as the band had finished their set Barney sprang into action on our behalf, already having sorted out the quickest route to the backstage hospitality area. He whisked us along our way giving off an air of importance to all passing onlookers as if we were something else special in the building. Arriving at our destination, we got past security as part of the management’s entourage and straight into the melee of early arrivals.

As the room began to fill up, I started to become in awe of the situation I was in. Not knowing what to do, I stood there with my 3 bandmates, also not sure about where to put themselves in a room rapidly filling up with strangers.

Barney had already gone into manager-mode and was working the room, chatting and passing on tapes to those he had identified as key players in the game. I was quite impressed by his natural bravado and fearlessness at approaching strangers, whilst I stood there like a useless spare mannequin. As the redundancy of my presence became more obvious, my level of discomfort began to rise, until I saw a tall, familiar figure approaching.

Boon is in the Building!

Dressed head to toe in black and cooly carrying off what must have been a very expensive, long coat, the unmistakeably rugged features of Boon Gould registered with my astonished eyes. Here I was in a club in London, standing but a few feet from the older brother of my current drumming hero, star-struck and paralysed to the spot. I exchanged glances with the Bass player and we both smiled at the surreal situation we were in.

At that moment, everyone else in the room became a background feature as I mentally gasped at the physical presence of an actual Level 42 member! Could Phil also be here? I thought, hoping desperately for that to be the icing on my fantasy cake.

Before I had chance to think, Barney swooped in on the quiet guitarist and I watched some sort of short exchange take place between them, culminating in one of our demo tapes voluntarily finding its way into one of the deep pockets of Boon’s coat, which I was already hopelessly coveting. Word was, Yojhi Yamamoto was kitting out Level 42 with his expensive designs, which were well out of reach for low income drummers like myself.

Barney gestured a signal to us as our green light to approach the most famous element in the room.

“This is Boon from Level 42!” Barney exclaimed, as if we needed telling.

Exchanging polite greetings, I mumbled something about looking forward to seeing the band later on in the year at the Birmingham NEC to which, Boon mumbled an appropriate but friendly response. Thinking back, I guess he was probably feeling a little uncomfortable and it wouldn’t surprise me if he’d plucked the short straw as a favour to the record label to attend the evening for PR purposes.

I didn’t push my luck and decided not to invade his personal space any further, though if I’m honest, I really didn’t have anything else purposeful enough to waste his time with. He didn’t stay around for much longer and I wondered afterwards how long our cassette of musical hopes stayed in his pocket. It was probably for the best if he’d binned it at his first opportunity; we were a dysfunctional entity by that point anyway.

After the After-Show

Nothing good happened for my band after we returned from London, deservedly so. We took this as a failure on Barney’s part and wasted no time in dumping him. That’s the kind of people we were at the time. Barney was just another time waster to us, hindering our way to the top. We used him as a willing volunteer, then ejected him without hesitation.

In truth, Barney was one of the good guys, an amicable trier, alive with enthusiasm and probably too honest for the music management game. If it hadn’t been for Barney’s keenness to push our product and make use of opportunities, I would have never had my brief chance encounter with Boon Gould. If I had possessed the same bravado and drive as Barney, then maybe I could have engaged with Boon in some meaningful musical conversation. But as the saying goes, I came close, but no cigar.

Bowing out Gracefully

I saw Level 42 two nights on the run at the Birmingham NEC in March 1987. By the end of the year, Boon exited from the band during their American tour opening for Madonna. The band’s press release cited nervous exhaustion as the reason and not long after, his brother Phil also took leave of the pop-circus hamster wheel.

For me, without the Gould brothers, Level 42 had lost half of what made them organically unique. Despite their replacement with high calibre musicians, as far as I was concerned, the band were a ship with half its rudder missing.

Both Boon and Phil spent the following years out of the spotlight, Boon appearing slightly more reclusive than his younger sibling. Boon did offer some contact with his fans via his own website and even managed to release some solo material. He also collaborated with his old band lyrically, whilst keeping a low profile. Pre-social media Level 42 fan websites also did their best to keep any activities of the Goulds publicised, even the keeping the fires stoked within the online forum community who refused to give up hope of an eventual reunion.

Level 42 did toy with the idea in the early 2000s, but the Mark/Phil musical divisions reportedly remained too deep to bridge. Sadly, the now sexagenarian musicians will never be able to test those waters again.

Although I often thought Boon looked a little miserable on stage, I prefer to remember him as he was in the promo video for ‘Something About You’, driving a classic open-top sports car, wind blowing through his hair, with the gorgeous Cherie Lunghi in the passenger seat. 1985 wasn’t such a bad year for music, after all.

Addendum

I came across this great tribute to Boon by long-time Level 42 fan, Julian Hall. He met the man many more times than I did and didn’t lose his nerve like me!